By Kulbir Dhillon, MSN, FNP, APNP, WCC

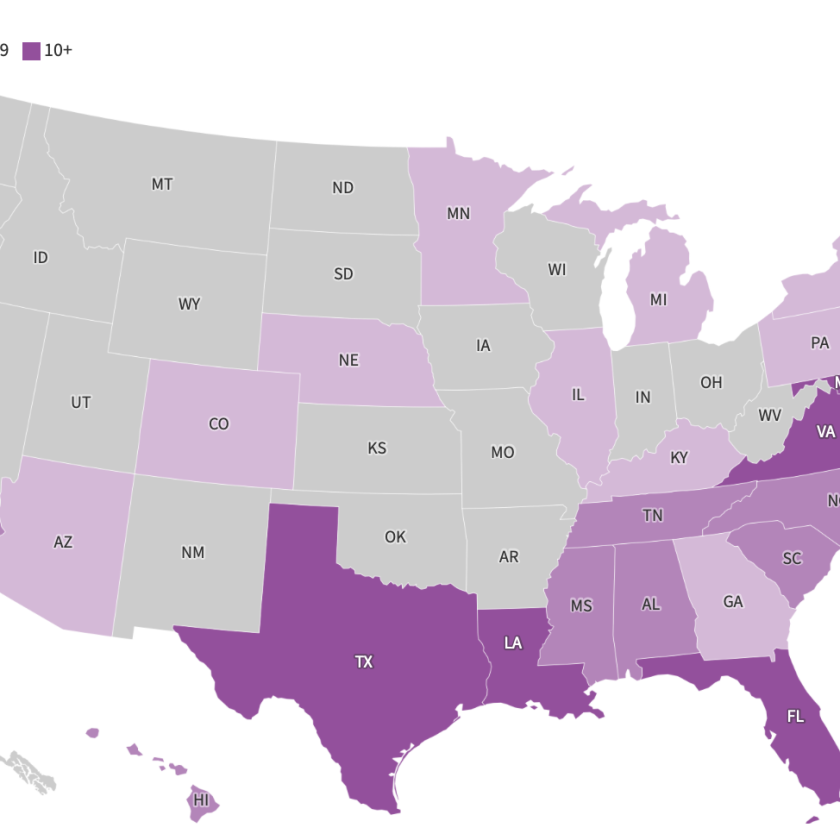

Venous disease, which encompasses all conditions caused by or related to diseased or abnormal veins, affects about 15% of adults. When mild, it rarely poses a problem, but as it worsens, it can become crippling and chronic.

Chronic venous disease often is overlooked by primary and cardiovascular care providers, who underestimate its magnitude and impact. Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) causes hypertension in the venous system of the legs, leading to various pathologies that involve pain, swelling, edema, skin changes, stasis dermatitis, and ulcers. An estimated 1% of the U.S. population suffers from venous stasis ulcers (VSUs). Causes of VSUs include inflammatory processes resulting in leukocyte activation, endothelial damage, platelet aggregation, and intracellular edema. Preventing VSUs is the most important aspect of CVI management.

Treatments for VSUs include compression therapy, local wound care (including debridement), dressings, topical or systemic antibiotics for infected wounds, other pharmacologic agents, surgery, and adjunctive therapy. Clinicians should be able to recognize early CVI manifestations and choose specific treatments based on disease severity and the patient’s anatomic and pathophysiologic features. Management starts with a full history, physical examination, and risk-factor identification. Wound care clinicians should individualize therapy as appropriate to manage signs and symptoms.

Compression therapy

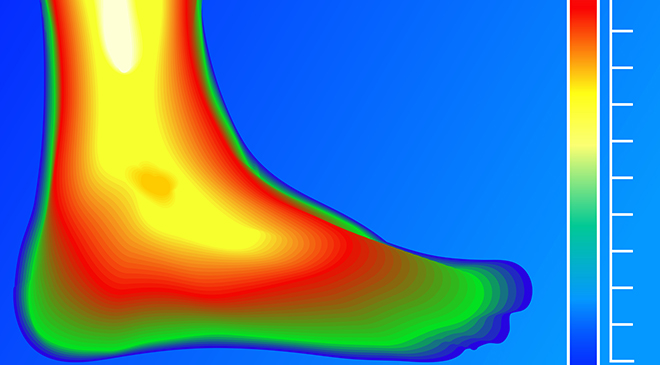

Treatment focuses on preventing new ulcers, controlling edema, and reducing venous hypertension through compression therapy. Compression therapy helps prevent reflux, decreases release of inflammatory cytokines, and reduces fluid leakage from capillaries, thereby controlling lower extremity edema and VSU recurrence. Goals of compression therapy are to reduce symptoms, prevent secondary complications, and slow disease progression.

In patients with severe cellulitis, compression therapy is delayed while infection is treated. Contraindications for compression therapy include heart failure, recent deep vein thrombosis (DVT), unstable medical status, and risk factors that can cause complications of compression therapy. Ultrasound screening should be done to rule out recent DVT. Arterial disease must be ruled out by measuring the ankle-brachial index (ABI). Compression is contraindicated if significant arterial disease is present, because this condition may cause necrosis or necessitate amputation.

High compression levels should be used only if the patient’s ABI ranges from 0.6 to 1.0. With an ABI between 0.9 and 1.25, the patient likely can tolerate treatment with four-layer compression or a long-stretch compression wrap. For patients with an ABI between 0.75 and 0.9, use single-layer compression with cast padding and a Coban wrap in a spiral

formation.

Keep in mind that use of a compression wrap depends on the patient’s comfort level and degree of leg edema. In patients who have mixed venous and arterial insufficiency with an ABI between 0.5 and 0.8, monitor for complications of arterial disease. Don’t apply sustained high levels of compression in patients with ABIs below 0.5. (See Comparing compression levels.)

Pneumatic compression

The benefits of intermittent pneumatic compression are less clear than those of standard continuous compression. Pneumatic compression generally is reserved for patients who can’t tolerate continuous compression.

Local wound care

Wound debridement is essential in treating chronic VSUs. Removing necrotic

tissue and bacterial burden through debridement enhances wound healing. Types of debridement include sharp (using a curette or scissors), enzymatic, mechanical, biologic (for instance, using larvae), and autolytic. Maintenance debridement helps stimulate conversion of a chronic static wound to an acute healing wound.

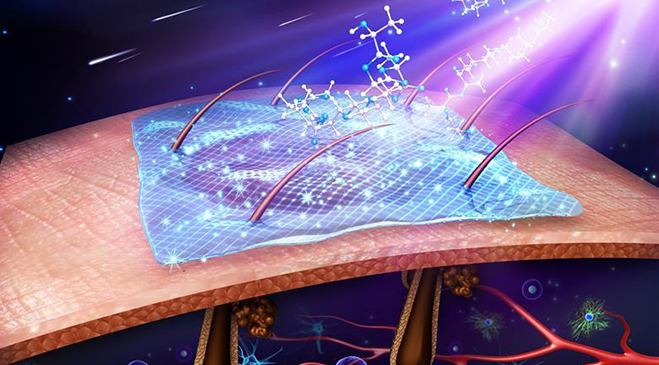

Dressings

Dressings are used under compression bandages to promote healing, control exudate, improve patient comfort, and prevent the wound from adhering to the bandage. Vacuum-assisted wound-closure therapy can be used with compression bandages.

A wide range of dressings are available, including:

• hydrofiber dressings

• acetic acid dressings

• silver-impregnated dressings, which have become more useful than topical silver sulfadiazine in treating VSUs

• calcium alginate dressings

• proteolytic enzyme agents

• synthetic occlusive dressings

• extracellular matrix dressing

• bioengineered skin substitutes. Several human-skin equivalents created from human epidermal keratinocytes, human dermal fibroblasts, and connective tissue proteins are available for VSU treatment. These grafts are applied in outpatient settings.

Antibiotics

Common in patients with VSUs, bacterial colonization and infection contribute to poor wound healing. Oral antibiotics are recommended only in cases of suspected wound-bed infection and cellulitis. I.V. antibiotics are indicated for patients with one or more of the following signs and symptoms of infection:

• increased erythema of surrounding skin

• increased pain, local heat, tenderness, and leg swelling

• rapid increase in wound size

• lymphangitis

• fever.

Progressive signs and symptoms of infection associated with fever and other toxicity symptoms warrant broad-spectrum I.V. antibiotics. Suspected osteomyelitis requires an evaluation for arterial disease and consideration of oral or I.V. antibiotics to treat the underlying infection.

Other pharmacologic agents

A wide range of other drugs also can be used to treat VSUs. (See Other drugs used to treat VSUs.)

Surgery

Surgery can reduce venous reflux, hasten healing, and prevent ulcer recurrence. Surgical options for treatment of venous insufficiency include saphenous-vein ablation, interruption of perforating veins with subfascial endoscopic surgery, and treatment of iliac-vein obstruction with stenting and removal of incompetent superficial veins by phlebectomy, stripping, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy.

Patients should be evaluated early for possible surgery. An algorithm based on a review of literature indicates that patients whose wounds don’t close at 4 weeks are unlikely to achieve complete wound healing and may benefit from surgery or other therapy.

To help determine if surgery may be warranted, assess venous reflux using duplex ultrasonography, which can reveal CVI, assess physiologic dysfunction, and identify abnormal venous dilation. Consider a vascular consult for surgical management of patients with superficial venous reflux disease or perforator reflux disease.

Surgery aims to correct valve incompetence leading to increased intraluminal pressures. (Venous valve injury or dysfunction may contribute to CVI development and progression.) Surgical reconstruction of deep vein valves may be offered to selected patients with advanced severe and disabling CVI who have recurrent VSUs.

The literature shows that surgical vein stripping isn’t superior to medical management. Endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), a minimally invasive procedure, yields greater benefits than vein stripping and other types of surgery.

Skin grafting

Skin grafting may be done in patients with large or refractory venous ulcers. It may involve an autograft (skin or cells taken from another site on the same patient), an allograft (skin or cells taken from another person), or artificial skin (a human skin equivalent). Skin grafting generally isn’t effective if the patient has persistent edema (common with venous insufficiency) unless the underlying venous disease is addressed.

Adjunctive therapies

Adjunctive therapies, such as ultrasound, pulsed electromagnetic fields, and electrical stimulation, can aid in treating VSUs that fail to close despite good conventional wound care and compression therapy.

Patient education

Be sure to teach patients with VSUs about treatment and prevention to promote successful management. Advise them to:

• elevate their legs above heart level for 30 minutes three to four times daily (unless medically contraindicated),

to minimize edema and reduce intraabdominal pressure. Increased intra- abdominal pressure in severely and

morbidly obese patients can increase iliofemoral venous pressure, which transmits via incompetent femoral veins, causing venous stasis in the legs.

• perform leg exercises regularly to improve calf muscle function

• use graduated compression stockings as ordered to prevent dilation of lower-extremity veins, pain, and a heavy sensation in the legs that typically worsen as the day progresses

• minimize stationary standing as much as possible

• treat dry skin, itching, and eczematous changes with moisturizers and topical corticosteroids as prescribed. (See Skin care for CVI patients.)

Also help patients identify risk factors for CVI (such as smoking and overweight), which can affect management. Teach them about therapeutic compression stockings, including their use, benefits, and care instructions. Remind them to wear stockings every day to prevent venous edema and VSU recurrence. Finally, urge them to adhere to the plan of care and get regular follow-up care.

Selected references

Abbade LP, Lastória S. Venous ulcer: epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(6):449–56.

Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Medical management of lower extremity chronic venous disease. Availabe at: www.uptodate.com/contents/medical-management-of-lower-extremity-chronic-venous-disease. Accessed December 4, 2013.

Baranoski S, Ayello EA. Wound Care Essentials: Practice Principles. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Bryant R, Nix D. Acute and Chronic Wounds: Current Management Concepts. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2011.

Habif TB. Clinical Dermatology: Expert Consult. 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2009.

Kimmel HM, Robin AL. An evidence-based algorithm for treating venous leg ulcers utilizing the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Wounds. 2013:25(9);242-50.

Kistner RL, Shafritz R, Stark KR, et al. Emerging treatment options for venous ulceration in today’s wound care practice. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2010;56(4):1-11.

O’Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ologun Y, et al. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003557.

Patel NP, Labropoulos N, Pappas PJ. Current management of venous ulceration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):254S-60S.

Wollina U, Abdel-Naser MB, Mani R. A review of the microcirculation in skin in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: the problem and the evidence available for therapeutic options. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2006:5(3);169-80.

Kulbir Dhillon is a wound care nurse practitioner at Mercy Medical Group, Dignity Health Medical Foundation in Sacramento, California.

DISCLAIMER: All clinical recommendations are intended to assist with determining the appropriate wound therapy for the patient. Responsibility for final decisions and actions related to care of specific patients shall remain the obligation of the institution, its staff, and the patients’ attending physicians. Nothing in this information shall be deemed to constitute the providing of medical care or the diagnosis of any medical condition. Individuals should contact their healthcare providers for medical-related information.

Very well written. I got alot out of this.

Good job!

Very informative.

with an ABI of 1.07 is high compression ok?

Overall, this was a well written article.

I have some concerns with your statement “High compression levels should be used only if the patient’s ABI ranges from 0.6 to 1.0.”

Full (High) therapeutic compression, applying less than or equal to 40 mmHg of compression at the ankle, is indicated for patients who are not in CHF and their ABI is greater than or equal to 0.9.

“Modified” not “High” compression therapy is indicated for patients not in CHF and their ABI runs between 0.6 and 0.8.

Any patient’s ABI equal to or less than 0.5, the clinician should not apply any compression to the extremity out of concerns of ischemia (necrosis) and should refer them to a Vascular Service since at this level, 50% or less of the blood flow going to the arm is going to the foot.

One should also be concern about the diabetic patient whose ABI is 1.3 or greater since this might represent calcified arteries with abnormally elevated ABI levels and the ABI should not be used for criteria for applying compression therapy.

Thank you,

Don Wollheim, MD

What is a “3 layer wrap” for stacis wound care?

It is a 3 layer compression wrap.

It’s a 4 layer wrap (Ex.,Profore) minus the 3rd layer (this is the long stretch layer that provides the majority of the pressure). Known as “Modified compression” used if the ABI is between 0.6 and 0.8.

I had 3 serious, extremely painful ulcers, one on the ankle of my right leg, one on the ankle of my left leg and one on the heel of my left leg. The one on the ankle of my left leg was almost 3 years old. A podiatrist judged that they were venous ulcers and sent me to a vascular specialist who after examination claimed that I had no vascular problems. After roughly 3 months of “care” and virtually no healing results and being told by my care-taker that his treatment (compression wraps , etc.) might take about a year and also being told that he was concerned about the possibility of amputation, I stopped going to the podiatrist about the same time my wife was at a feed store getting some stuff for our animals and noticed a tube of EMT GEL, a wound care for large and small animals. She purchased a tube and I have been using it for about 3 months and at this time all of my wounds have healed.

Richard Washell

March 13, 2016

Very informative I have venous ulcers for over 25years an it’s been a struggle I’ve yet everything to help cure or limit the conditions.I had 3 stents in my pelvic,8 leg ablation,skin grafts an now I’m trying a wound-vac looking for closer.my question is if this should help with closer should this keep the wound closed with compression